MUSIC TO HEAR, Joseph Summer’s follow up to WHO IS SYLVIA from Navona Records off his Shakespeare Concerts set, is the result of the composer’s lifelong obsession with poetry. The album pairs the works of contemporary poets as well as Shakespeare with Summer’s music in order to express deeper significance than either words or music are capable of on their own.

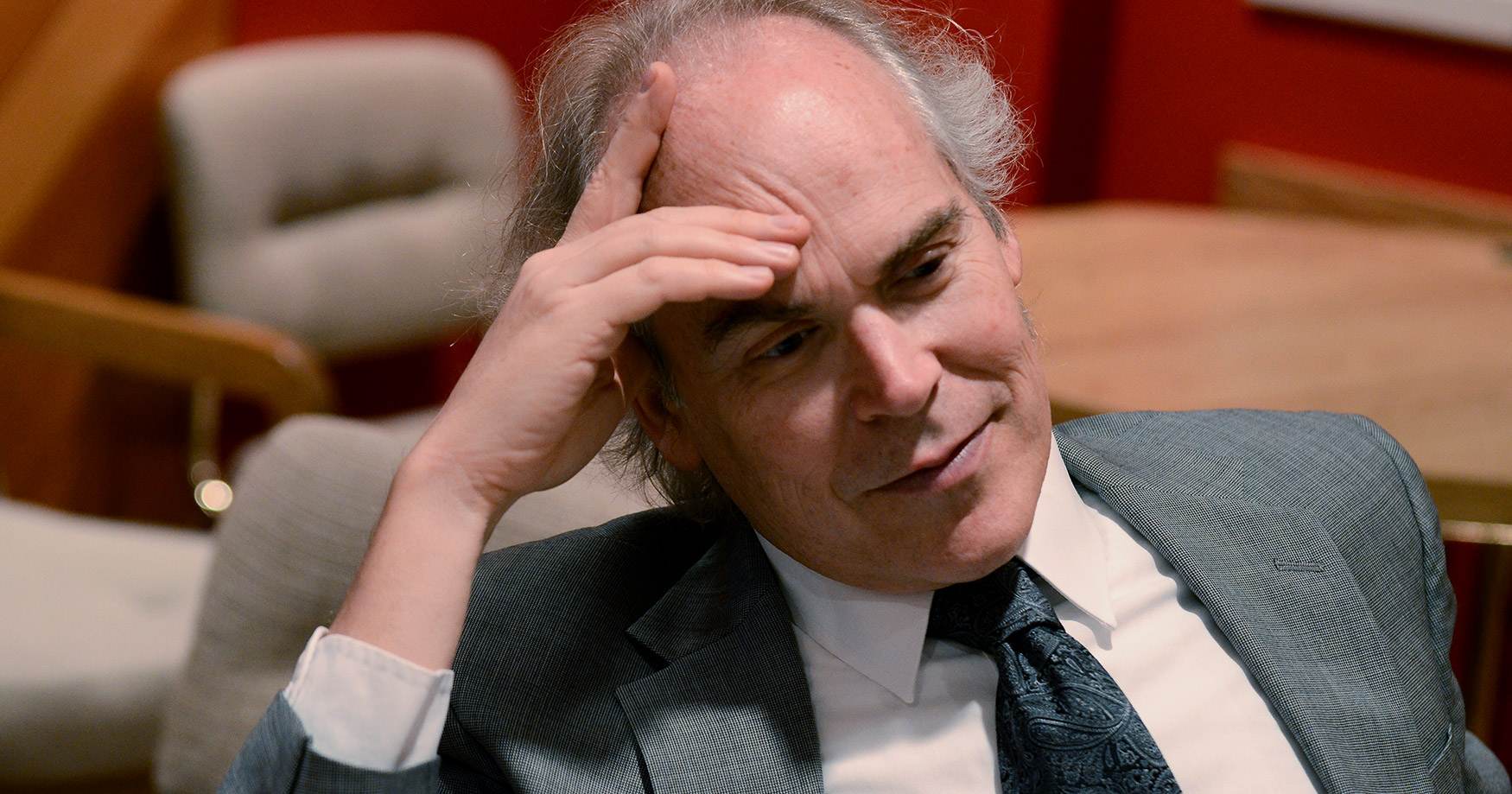

Joseph is our featured artist for “The Inside Story,” a blog series exploring the inner workings and personalities of our composers and performers. Read on to discover how trying to flag down a rescue boat at sea inspired him to write…

If you weren’t a musician, what would you be doing?

In 1984, after the birth of our daughter, our assets were zero. I’d previously made a promise to myself that our financial situation must never become unsalvageable. The lack of funds seemed like judgment by the universe that my composing career was over. I had no interest in pursuing composition after a hiatus as a pizza huckster. If the muses didn’t think my compositions were worthy of support enough just to live, then I would heed their animadversion.

I made an appointment with a nearby pizzeria to apply for a job. Walking out the door of our apartment on 46th and Cedar in West Philadelphia, on the day of the job interview, I stopped to wave farewell to my wife, as she held our dear (emotionally and financially) infant daughter, and opened the mail box. Inside was an envelope from the IRS. I opened it and discovered – to our surprise – a check for about $800, an “earned income credit” refund from the government for our reproductive success. We’d had no idea such was due us. Now we had another three months leeway in our financial situation. (We lived cheap in the eighties.) I insisted on going to the interview; and Lisa insisted on coming (with our baby) as well. I was offered the position, but turned it down, with relief. The owner gave us free pizza, anyway.

What advice do you have for young musicians?

My career is founded on unreasonable risk, so my advice – which would be horrendous – would be to throw caution to the wind and pursue your unrealistic dream. When I was in my early twenties I concocted an absurd scheme to compose large scale operas in a musical climate that was unreceptive to new opera; and figure out how to get my music produced later. Later. Monstrously anserine. My wife supported us financially, with a career in music therapy, which meant we had to live close to the bone; and once we decided to have a child, that career was ended. We lived on food stamps and WIC for a year. Then, after a surprising gift from the IRS extended our lease on a dream, she wanted to go back to work – she’d had enough full time mothering – and was able to find a new career in academia, as the director of a music therapy program in Tennessee. Eventually my music garnered some success, though not remuneratively speaking; not that that is a problem, thanks to my wife, Lisa. I don’t think I can give any rational advice to young musicians.

Tell us about your first performance.

I’m going to talk about the first performance of my first decent composition, not my first performance as a French hornist (which was an arrangement of Brahms’ first symphony themes for student orchestra when I was eight) nor my first composition performance (which was a brass sextet with two tubas; in around 1968). In the summer of 1971, I’d been studying with Karel Husa intensively for a couple weeks, in North Carolina at Eastern Music Festival, and had written four duets for oboe and bassoon. Husa was immensely pleased with the duets and placed them on an afternoon new music concert July 28, 1971 at Dana Auditorium. Husa was the éminence grise of the concert but he decided that my duets needed his personal attention, so he entered the domain of this student composition concert and – all six and a half feet of him – conducted a duet by a fifteen year old (sans credit in the program). I would like to think that this world renowned composer/conductor never before nor after conducted a duet on a concert stage.

What are your other passions besides music?

When my wife and I aren’t working, we enjoy the ocean. If we could live under water we would. At least twice a year we sojourn in Indonesia, spending our days and nights diving. One year, 2012, we almost didn’t come back. Diving in the Indian Ocean, south of Lombok, we were left at sea by the dive boat. Battling rough seas, a swarm of Portuguese Man-O-Wars, exposure, and a host of other life-threatening predicaments; we swam for a day to a deserted rocky beach where we foraged to survive, eating raw fish and snails. After a night in a neighboring jungle we climbed a mountain as a search-and rescue helicopter – garbed in attractive orange paint – circled above, looking for us. They couldn’t see us through the thick foliage. Eventually we made it to the village of an indigenous tribe, the Mekaki, and an anti-terrorist army group that was searching for malefactors heard about us, and clambered down to the village to “rescue” us. I was pretty beat up, broken ribs and deep lacerations, plus other issues; so I couldn’t dive for a week. My wife took a little longer to venture back, but she did.

What inspires you to write?

I find I don’t need “inspiration” to write. I wake up, perform my ablutions, and get to work. However, that is not to say that external events don’t influence me. I’m inspired by everyday occurrences or the unusual. For example, after my wife and I had survived our eight hour swim through ten foot rolling waves to find ourselves on a deserted beach, and after we’d filled our bellies with live snails, and assayed our situation, and after we’d found a dry creek bed within which to sleep: that night I found myself hopelessly signaling a passing squid boat (with my dive torch) and – though disappointed by the boat’s disinterest – was enthralled by the vision of hundreds of crabs molting on the rocks in the light of the moon. That made me think of Caliban in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, when he says “let me bring thee where crabs grow.” After returning to my studio in America, I began work on a trio in the Tempest set on the beach upon which Trinculo and Stephano have found themselves after they have swum to shore from their sinking boat, to become intimates of Caliban.

If you could collaborate with anyone, who would it be?

I set a boatload of poetry, mostly Shakespeare and my own; but I also set texts of living (and recently deceased) poets I know or have known. Unfortunately, I have not been able to communicate with the poets with whom I’m familiar: our collaboration requires preparation and cooperation. The disjuncture arises not out of the difference between the creative act of the composition of words versus music; but rather – I believe – from the poets’ lack of understanding that one cannot just ask a pride of string players to show up at a jam-packed used book store and play a theretofore unseen score while a soprano sight-sings a poem in 5/8. How many times have I said, “I’d love to; but first I have to pay an engraver, then hire a soprano and a quartet, then we need a week of rehearsal,” only to see the poet’s dead eyes turn back to his beer. I put my hand to my head, nursing my tea – whose order was rewarded with some expected mockery – and think how much easier it is to collaborate with the dead.

MUSIC TO HEAR

MUSIC TO HEAR from Joseph Summer is available now from Navona Records. Click here to visit the catalog page and explore this album.

WHO IS SYLVIA

WHO IS SYLVIA from Joseph Summer is available now from Navona Records. Click here to visit the catalog page and explore this album.